To make up for the lack of recent posts on here, I thought I would upload a rather lengthy presentation which I recently did for a conference on Victorian studies. The theme for the session I was in was intergenerational tension, and my presentation looked at why this was often lacking in cycling clubs during the 1890s. Hope there are some areas of interest/some people manage to make it to the bottom!

–

Hello. I am sure I would not be stood in front of you today as someone who has spent a year of their life writing a 40,000 word dissertation, if I had not found a set of sources which have been in themselves a constant source of pleasure and interest to me. From my perspective at least, there are two main reasons why primary material on late nineteenth-century cycling is so wonderful.

The first is that all editions of Cycling, the largest cycling magazine from the 1890s, are digitised and word searchable, which has saved me countless hours of trawling through paper copies. The second, is the collection of cycling club gazettes from this period which can be found in archives throughout the country. These gazettes were produced by members of clubs for members of clubs, and as such provide very readable, revealing and perhaps above all else, humorous accounts of the activities which members of these institutions engaged in.

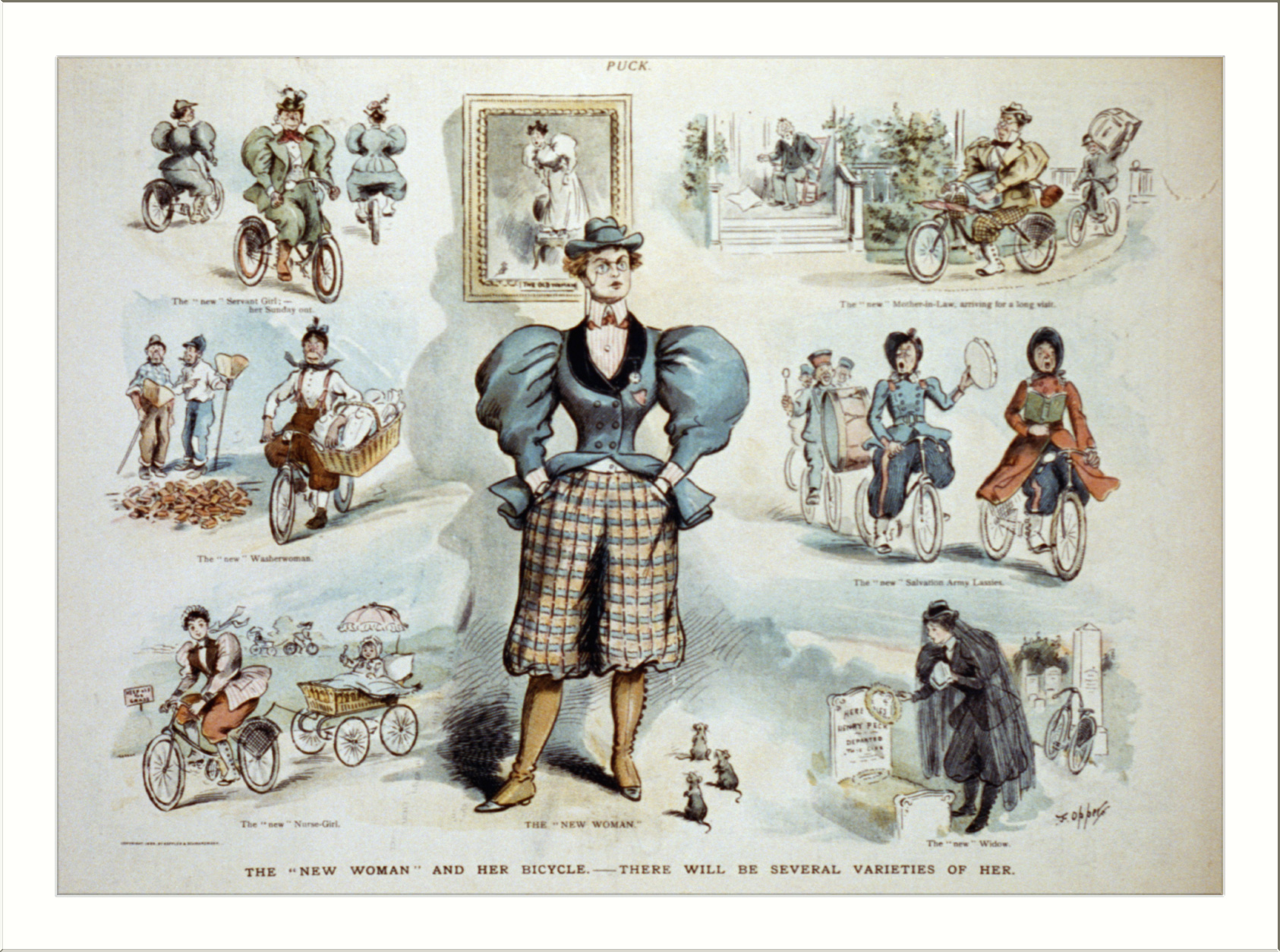

A good example of your typical 1890s cycling club can be found in this photo of the Boulevard C.C. from near Nottingham. Clubs were for the most part home to men from the middle and lower-middle classes, and whilst the growing popularity of cycling with women during this period saw many clubs developing ‘ladies sections’, creating two distinctive sections allowed the male members to, for the most part, enjoy their activities in exclusively male company. The primary function of cycling clubs in this period was weekend ‘club runs’, in which members would spend an afternoon going for a group ride, typically between twenty and sixty miles out into the British countryside. Central to these ‘runs’ were stops for food and liquid refreshment at pubs and inns, which, along with the rides themselves, afforded plenty of opportunity for sociability between members.

Certainly what I view to be one of the defining features of cycling clubs in this period was how they were home to members in very different life stages, which if you look hard enough, is evidenced in this photo. Census records reveals that the ages of members of clubs regularly ranged from late teens to forties and fifties. This variety of ages is demonstrated in the nicknames of members of the Stanley C.C. from Derbyshire, which ranged from ‘the boys’, to ‘uncle’ and ‘grandpa’, as well including, ‘the boys of the old brigade’.

It is not this range of ages which makes cycling clubs such an interesting site of historical study. Middle-class homes, workplaces, schools and universities were all sites in which men of different ages spent plenty of time in each other’s company. What makes these sites so distinctive is rather the relationships which existed between middle-class at different stages in the lifecycle. Unlike these other sites, I would argue that the relationships between members of clubs of different ages would frequently be defined by sociability, friendship, admiration and affection.

This is not to say that such relationships wouldn’t have existed between middle-class fathers and sons, employers and employees, or teachers and students during the late-nineteenth century. However, existing studies of intergenerational relationships such as these, give a far heavier emphasis to the tensions which existed between middle-class men of different ages.

For example, Paul Deslandes’ work on late-nineteenth century Oxbridge has highlighted the conflicts which often existed between undergraduates and their dons. It is argued that,

‘The administrative and academic power of the college fellow, tutor, dean and university official was always seen as a threat to youthful manhood. Undergraduates…expressed a general distrust of all dons, regardless of chronological age or athletic propensities, and in doing so they fostered generational tensions and emphasised the impossibility of egalitarian friendships between these two segments of the university community.’

Studies of middle-class fathers from the Victorian period also highlights the often difficult and distant relationships which they had with their children. The ‘cult of motherhood’ established during the early nineteenth century, placed a much heavier emphasis on middle-class mother’s providing their children with love, care and affection than their fathers. Whilst John Tosh has recognised that Victorian fathers could enjoy intimate relationships with their children, his three other models for these relationships, in absent, distant and tyrannical, recognise the often limited relationships which existed between middle-class fathers and their children in this period.

This paper will explore the factors which, by and large removed the tensions which could be found between middle-class men of different ages in homes, workplaces and universities, and instead created different models of intergenerational relationships within late-nineteenth century cycling clubs.

Now, it can be recognised that tensions between middle-class men of different ages often emerged due to imbalances in power and authority. Middle-class men in their late teens and early twenties might often resent the authority and power wielded by those older than themselves, seeing it as something to be distrusted and even challenged. Whilst these imbalances were not necessarily a source of tension, they would certainly have placed barriers in the way of men of different ages forming relaxed, friendly and sociable relationships with each other.

I would argue that such dynamics were much less prevalent in cycling clubs. These were voluntary institutions, focussed around members shared interest and enjoyment of cycling. This immediately placed the relationships between members of different ages on a different footing compared to the home, workplace, school or university. Their relationships were built much more upon a common enthusiasm, than differing levels of power and authority.

As well as this, the activities of cycling clubs took place in men’s leisure time. This meant that members shared a mutual desire to engage in activities which they found to be enjoyable, relaxing and pleasurable whilst in the company of like-minded individuals On-top of their common interest in cycling, members of different ages possessed a common desire for sociability and friendship with each other.

This is not to say that members of different ages would always find pleasure and enjoyment in the same activities. Unlike team sports such as football or cricket, there were no rules stating how members should engage in the pastime of cycling. This meant that when on ‘club runs’ or group rides together, there were plenty of opportunities for younger and older members to engage in separate activities.

For example, an article in the gazette of the Stanley C.C., written by a more senior member of the club, stated how during a stop at a park during a ‘club run’

‘Under the chestnut trees I focussed the boys, and then they ran away to the top of Bury Hill. Magnificent scenery all around here, but too much for my poor camera.’

Clearly, ‘the boys’ did not share in the writer’s interest in photography, nor the writer their enthusiasm for rushing up hills. As well as this, it is apparent that members of different ages held differing levels of authority and responsibility. The age of the writer meant he represented some form of ‘authoritative’ figure, who would encourage ‘the boys’ to engage in certain activities whilst he partook in others.

However, it can be recognised that the nature of this authority was much softer than would often have been found in homes, workplaces or universities. The writer of the article did not tell the club’s younger members how to behave, but instead ‘focussed’ them. By doing so, the writer of the article was looking to give both himself, and the younger members of the club, the space and opportunity to engage in different activities which brought mutual enjoyment and pleasure.

Moreover, even when older members of clubs did take on more authoritative roles, this authority seems to have frequently been a source of admiration and respect rather than resentment. This was particularly the case when more senior members of clubs helped with the physical training of those younger than themselves.

Clubs in this period would often organise inter-club ‘race meets’, in which members of each club would compete in various races, with the winners scoring points for their clubs. Older members would often act as mentors to those younger than themselves who were in training for these events, providing them with advice and support, which was in-turn valued and appreciated. An article in Cycling on a more senior member of the Polytechnic C.C. described how,

‘The polytechnic racing boys of to-day look up to Leach as a kind of benevolent father figure, whose advice must be followed at any cost, and the good show, made by the Polyites in their recent match with the Catford, was to a great extent, due to the fatherly solicitude of Leach.’

Now, this quote does highlight how the relationships between members of different ages were not completely removed from those which might exist in sites such as the home- the nicknames ‘Uncle’ and ‘Grandpa’ which were given to members of the Stanley C.C. reinforce this point.

However, compared to father sons relationships I would argue that the interactions between older members and those they mentored within cycling clubs would have been much simpler, being focussed almost exclusively around their shared goal of winning races for their club. This would have helped remove tensions which might have existed in certain aspects of father son relationships, and ensured that differing levels of knowledge and experience would be a far more frequent cause of respect and admiration. Indeed, such dynamics can be recognised to more closely resemble relationships which might have existed between young men and their uncles and grandfathers, which in-turn can explain the nicknames given to older members of the Stanley C.C.

In the last part of this presentation, I will look to move these arguments on, and argue that the relationships between members of different ages could sometimes break free from connotations with authority and power, and instead be defined by friendliness and sociability.

Now, whilst cycling club members in different stages of the lifecycle would often engage in activities separately or differently to each other, the goings-on of clubs also gave plenty of opportunity for joint excursions and adventures. ‘Club runs’ might involve all members of the club cycling together at a pace which suited both the younger and older members. As well as this, stops for food and drink at pubs created opportunities for members of different ages to interact and socialise with other more or less as equals.

Joint activities, engaged in by member’s young and old, allowed for more senior members to, on occasion, throw off their home and work identities, and behave in a much less restrained and ‘dignified’ manner. An article in Cycling, titled ‘It makes you young again’, described how,

‘Cycling seems to possess a potent and peculiar charm to the middle-aged, aye, even the elderly man. It is not unusual to see the swarthy, bearded man, the sober head of a business house, perhaps, and perchance the father of grown-up children, cutting capers that would put to shame the rollicking fledgling of some sixteen summers. It is no uncommon thing to see the man of forty, in company with a party of younger men, acting in a manner that seems positively childish, when considered, though at the time the circumstances would hardly warrant your thinking so.’

‘We have often noticed this levelling influence of the sport, and when you see bearded men- rulers among men we may say, vaulting five barred gates, turning somersaults, and otherwise sacrificing the dignity and discretion that is generally supposed to pertain to age for the frolicsomeness of youth, you cannot help believing that cycling does in reality give man a new lease of life.’

Imbued with ‘a new lease of life’.

Even if younger members were not ‘turning somersaults’ along with those older than themselves, witnessing more senior members throwing off their ‘dignity and discretion’ was an undoubted source of entertainment and amusement for them. A more junior member of the Stanley C.C. described how when on a club run,

‘The old ‘uns- I refer to William and Charles- began to show rare sprinting powers. It only required a little encouragement. I rode alongside Charles and hinted that William fancied himself at riding. Charles remarked that ‘he could beat his head off’. ‘Betsy’ sidled up to William and said that on the next level bit Charles had announced his intention of taking his number down. We gradually brought the two together, and taking a glance at each other, they were off for a couple of miles- the two ‘who ride only for pleasure’ were plugging away for all they were worth. I do not know how it finished; ‘Betsy’ and I laughed so much we could not keep up with them, but both admitted to me afterwards that they did not think the other would ‘come that game again’.

This quote highlights how older members of clubs did not simply return to a youthful state of existence when they joined up with their club mates on a Saturday. The reason the sight of William and Charles racing was such a source of amusement to the two other members was that it challenged their usual demeanour of being two more senior, dignified individuals who would ride ‘only for pleasure’.

However, it does show how cycling clubs did provide opportunities for men in later stages of the lifecycle to on occasion leave behind their ‘dignity and discretion’, in favour of more frivolous and carefree behaviours associated with men much younger than themselves. It can be recognised that older members of clubs were not only much ‘softer’ authority figures when compared to fathers, employees and teachers, but could also leave behind notions of authority altogether, which created new opportunities for sociability, friendship and humour between men of different ages.

I am aware that such arguments do not exactly conform to the theme of this session. However, I hope this paper has at least provided a couple of insights into the topic of intergenerational tension, and perhaps some useful reminders when we are studying it.

Firstly, common interests and enthusiasms could cut through differences in life-stages, and help soften the boundaries separating individuals at alternative stages of the lifecycle. Whilst a lot has been written about the role of the middle-class father in the Victorian home, there have been far fewer studies of their relationships with their children in other sites. Seaside holidays and joint memberships of leisure and sporting associations such as cycling clubs (which club journals reveal did often exist) would have lent themselves to very different intergenerational dynamics compared to domesticity.

Secondly, we should be wary of basing too much of our understanding of those we are studying on the attributes which their society attributed to individuals of their age. The identities men and women had at the age of twenty had not completely disappeared by the time they were forty, but remained in some way a part of who they were. Younger selves could, if only for a brief period on a Saturday afternoon, be re-experienced and re-enjoyed. I can think of no better way of ending my paper than by using two quotes to re-illustrate this point.

The first is from a member of the Bristol Bicycle and Tricycle Club, and describes the joys of cycling in South Devon and visiting sites associated with the Spanish Armada. The writer told the club’s other members that a cycling tour in this area would allow you to,

‘Forget your cosmopolitanism and every other ism, again a British boy and proud of it. Remember Nelson and Wellington, those brave tars and soldiers who prevented the Corsican usurper from ever planting his foot on old England’s shores. Presently you’ll find yourself humming, strumming and shouting as of yore, two skinny Frenchmen, one Portugese, one jolly Englishman can lick ‘em all three.’

‘In imagination become a boy once more, and again experience that exultation that fired you when you first read ‘Westward Ho’, and when you took two slabs of wood and a tintack and made a sword with which you slew scores of moustachioed Spaniards, and rescued fair damsels and countless treasures (not forgetting the treasures) from their clutches.’

The second is by a member of the Stanley C.C., describing their experiences of visiting an annual ‘cycling camp’ in Harrogate. These were large scale events in which members of clubs from across the country would meet up for a long-weekend of camping, frivolity and late-night drinking, occasionally interspersed with some cycling. It was described how,

‘Social distinction, rank of fortune, vanishes as you take your place at the shrine of Bohemianism, equal in one accord- the desire to knock as much enjoyment as you can into 4 days of grace. Can it be wondered then that men grown grey, be-bearded solemn pards, faced with the inevitable scourge of time, take to Harrogate as a duck to water, and for a brief spell throw aside the decorum and dignity incumbent with their station in life, to revel as they did in the heyday of their youth when the blood ran freer and the pulse beat quicker? Such enthusiasts can fully endorse the poet’s couplet,

Tho age is on his temple hung,

His heart, his heart is very young.’