Newspaper obsessions with cycling accidents in the 1890s (talked about in the previous blog), were not just recognised as being a bit ridiculous by the cycling press. In October 1897 Punch, in usual satirical vein, used newspaper descriptions of cycling accidents as inspiration for an article titled ‘Wheel Wictims’. The article detailed some cycling ‘accidents’ which they claimed to have strayed from the pages of the St James Gazette (a London evening newspaper from the period).

The lesson? Perhaps that no matter what the time period, worries about people participating in new social practices and activities will always make for good satire.

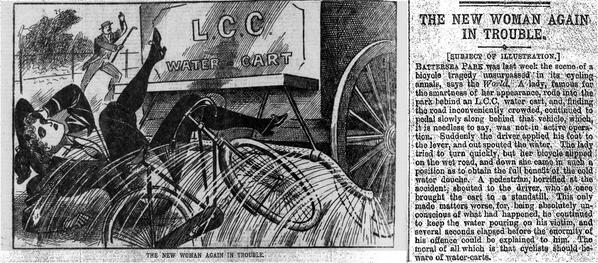

Description of a Cycling Accident from 1900. Source: http://www.bedfordshire.gov.uk/CommunityAndLiving/ArchivesAndRecordOffice/PathstoCrime/Takingatestdrive.aspx

‘The long and terrible list of bicycling accidents, which (at this time of year) we publish daily, still continues to grow. The latest batch is more alarming than usual, and proves conclusively that no one with the smallest respect for their safety should ever be induced to ride a bicycle. There are some persons who seem unable to relish any amusement that is not fraught with peril, but to such we would recommend bathing in the whirlpools of the Niagara as, on the whole, a less dangerous recreation.

From the highland village of Tittledrummie comes the news of one terrible disaster. As James Macranky, a youth of fifteen, was attempting to mount his machine for the first time in his father’s garden, the unfortunate lad lost his balance and was precipitated into the middle of a gooseberry-bush, with the result that his right hand was severely scratched. Although he is still alive at present, it is highly probable that he will develop symptoms of blood-poisoning in consequence of his misadventure, when tetanus will certainly supervene, and the fatal bicycle will once more have brought one more victim to a premature death.

What might have been a fatal accident was averted by the merest chance in Kensington on Monday last. According to an eye-witness of the thrilling scene, a young lady was riding by herself (a dangerous practice which we have repeatedly censured) along the Cromwell Road, when a hansom-cab suddenly appeared, advancing rapidly in the other direction. With marvellous nerve the young lady guided her machine to the left hand side of the road while the cab was still fifty yards from her, and was thus able to pass it in safety. But supposing she had lost her nerve in this alarming crisis, and had steered straight for the horse’s feet, she could only have escaped destruction by a miracle.

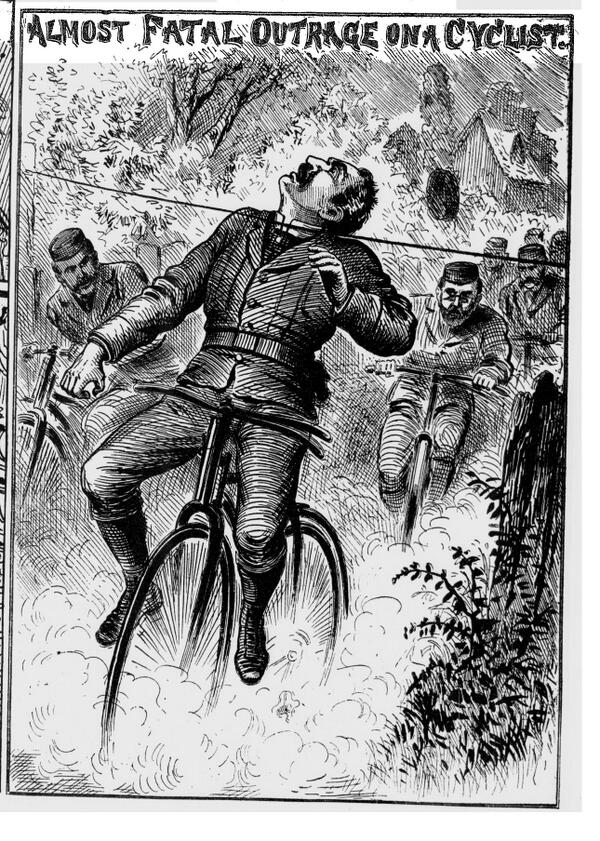

Cartoon of a lady engaging in the ‘dangerous practice’ of ‘velocipeding’. Source: http://fitisafeministissue.com/2013/03/

We are loath to inflict too many of these gruesome stories upon our readers, so will only add one more for the present, which may well serve as a warning to all those who tour in districts unknown to them. A party of ladies and gentlemen made an expedition on bicycles last week in the neighbourhood of Beachborough. Being unfamiliar with the locality, they dismounted at the point where two cross-roads meet, and hesitated as to which direction they should take. By a providential chance, they decided to keep to the left, and so reached their destination in safety. Afterwards they learned with horror that had they chosen the other road, ridden two miles along it, turned to the right, and then to the left again, they would have found themselves close to the edge of the cliff, from which there is a sheer drop of some six hundred feet to the beach beneath! And there are still some foolish persons who attempt to deny the perils of cycling!’

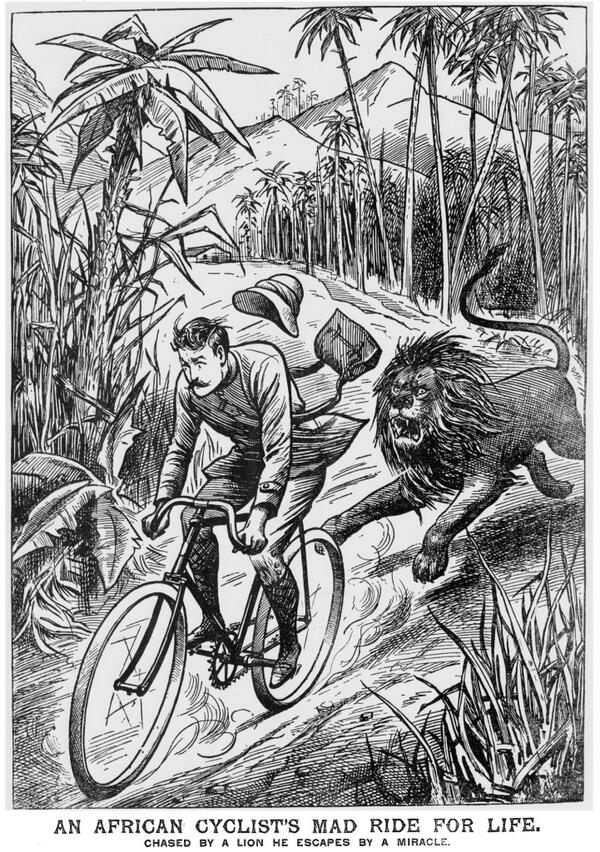

One of the historic ‘perils of cycling’. Source: http://www.mortaljourney.com/2011/03/all-trends/penny-farthing-bicycle-and-the-history-of-the-bicycle