As was recently discussed, men and women living through the 1890s rarely relished the prospect of mastering the art of cycling. Learning how to maintain your balance whilst pedalling forward on two wheels was a wobbly and often hazardous process, which could leave shins, knees and various other body parts battered, bruised and injured.

As I am sure all of us who have fallen off bicycles in public spaces are aware, being unceremoniously flung from a saddle, or slowly collapsing as you vainly attempt to unclip cleats from pedals, is also highly humiliating. However, for 1890s gents, and, in-particular ladies, the embarrassment of publicly parting company with a bicycle would have, in all probability, been even more acute.

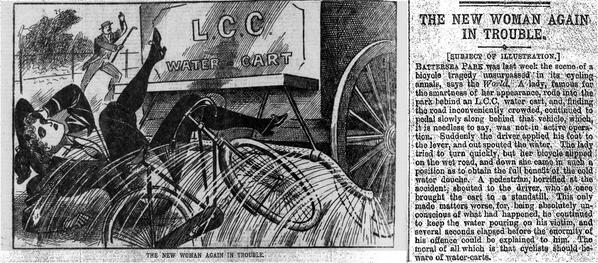

Article on a ‘New Woman’ falling off a bicycle. Source: https://storify.com/DigiVictorian/tit-bits-from-the-illustrated-police-news

Other blogs have highlighted how during this period, there were huge pressures on female cyclists to pedal their machines in a manner which was seen to be graceful and elegant. Whilst the 1890s saw discourses of middle-class femininity become reconciled with the notion of women on bicycles, they still expected ‘the fairer sex’ to cultivate more genteel and dignified riding styles than their male counterparts. Women who ‘scorched’, wore rational dress or who appeared red faced whilst cycling, could expect to be denounced as being inappropriately and dangerously ‘masculine’ in the cycling and wider press.

As such, learning to ride a bicycle required middle-class women to carefully navigate their way through a set of highly conservative and rigid gender norms. How could you learn to ride a bicycle without being seen as undignified, clumsy and inelegant?

‘Maidens with a disregard for convention’ by William Gordon Davis, 1895. Source: https://wellcomehistory.wordpress.com/2014/07/11/women-and-cycling/

Some found a solution to this problem by learning to ride at times of day when the roads they practised on were quiet, such as early in the morning or late at night. Others utilised roads away from city centres which were subject to little traffic. Both these practices can be seen in an article that appeared in The Aberdeen Weekly Journal in 1896, a piece which also recognised how quiet and remote spaces could be employed for purposes other than induction into the mysterious art of pedalling a bicycle. The article described how ‘Albyn Lane, the once secluded vernal bye-way sacred to whispering lovers’, had become a place where,

‘Any fine evening maidens may be seen acquiring the art of cycling with the aid of their male friends and advisors, and the comicalities of the situation- the ill-concealed flirtation- the agonising efforts to sit on a bicycle- form a spectacle worth a visit.’

Albyn Lane as it appears today

However, the growing numbers of middle and upper-class men, and, to a greater extent women, who wanted to learn how to ride bicycles without embarrassing themselves in public, not only led to cyclists flocking to previously ‘secluded vernal bye-ways’. The rising demand for more private spaces in which those on comfortable incomes could learn to cycle, also meant that from the mid-1890s onwards there was a rapid growth of so called ‘cycling schools’. An article on these schools, or ‘academies’ as they were also known, published in Cycling in 1896, described how,

‘Schools for cycle teaching have been in vogue for twenty years…but it required the advent of the better classes into our ranks, especially the female portion thereof, to create the schools we have with us on all sides at the present time.’

Cycle schools were typically based in large indoor spaces, such as halls or gymnasiums. Another article in Cycling, which gave details on a new cycling academy which had opened in Newcastle, stated how,

‘Mr T.D. Oliver…has opened the new gymnasium at Newcastle as a school for cycling… (His) enterprise in this direction is bound to secure a fair amount of patronage during the winter months, particularly from the fairer sex. The hall has an area of 5,300 feet available for cycling.’

Poster for a cycling school. Source: http://www.oldbike.eu/museum/1900s/fashion-costumes/mens-cycling-costume/

The costs of attending these schools were roughly similar to those outlined in the poster above- around two shillings (roughly £6.50 in today’s money) for a lesson, or 10 shillings sixpence for ‘full tuition’ (around £33-£35). These prices covered the expense of hiring a bicycle, and being solicitously guided by a so-called ‘master’, who would carefully and efficiently induct you into the art of pedalling a cycle.

Well that was the theory. Certainly the proprietors of cycling academies were usually respectable, well-renowned men who had many years cycling experience. A popular cycling school in Birmingham made much of the fact that their main instructor was ‘Professor J.M. Hubbard’, although what exactly his field of academic expertise was, and whether it was at all related to riding bicycles, was never made clear in their adverts.

However, beneath these ‘head masters’ were usually a number of young, male employees, who found a fairly easy, if moderate income by bequeathing their knowledge on how to ride a bicycle to others. Their method of teaching appears to have been fairly simple- they would typically put their arm around the side of the cyclist they were mentoring, and guide them round a track until they felt comfortable and confident enough to cycle by themselves.

Frances Willard receiving female support whilst learning to cycle.

It would appear that the women who were on the receiving end of the verbal and physical instructions of sweaty and, in all likelihood, rather awkward adolescences, did not always fully appreciate their teaching methods. A piece in Hearth and Home, a publication aimed at women from the middle classes, bemoaned the fact that in most cycling schools,

‘The average teacher, generally a raw youth, considers the whole duty of instruction is to hold the timorous tyro on her machine, but the masters at St. George School have a happy knack of quickly placing a rider en rapport with her bicycle.’

To avoid the awkwardness of physical contact between trainer and trainee, some schools implemented alternative forms of instruction. Another piece in Hearth and Home stated how,

‘The best instructors provide a leather belt for their pupils with a handle on the back, a method far preferable to being held on one’s machine by a perspiring youth.’

Learning to cycle on the road (and avoiding awkward young men)

However, not all women who attended these schools resented being held on their machines by ‘perspiring youths’. Indeed, such teaching methods appear to have occasionally been conducive to the types of romancing which occurred on Albyn Lane. An article in Cycling from 1896 described how,

‘A youth of some nineteen summers, employed in one of the large cycling schools, to teach ladies to cycle, recently captured the heart and hand of one of his fair pupils, and married her without delay. As the lady is well endowed with this world’s goods, the fortunate youth has no further necessity to teach cycling, except as a recreation’.

Let us hope their marriage out better than other instances when young men of humble means won the affections of women ‘well endowed with this world’s goods’ after experiencing close physical encounters with them.

City Bicycle School, Aldgate, London, 1883.

LikeLike

I have the ‘Lett’s Guide to the roads of England and Wales, an itinerary for cyclists, tourists and travellers’ 1884 edition which contains an advertisement for the North London Cycling and Tricycling School.

“single lesson 1/6 cycling guaranteed 10/6

tricycles lent on hire

proprietor W. H. Sargent

9 Brecknock Road, Camden”

LikeLike